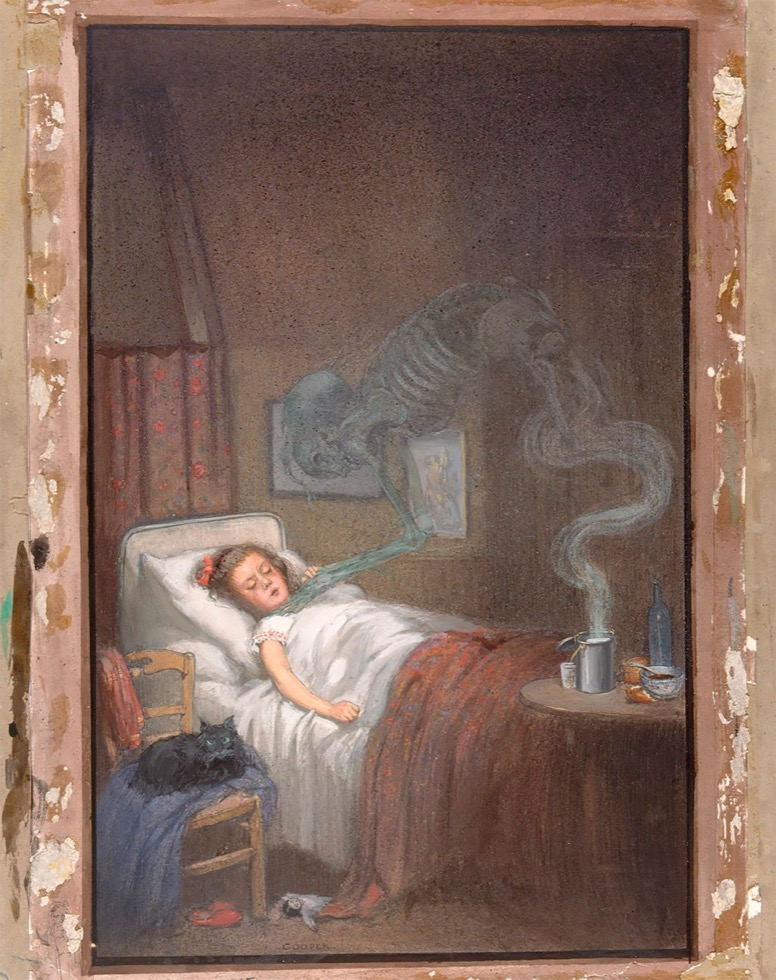

The Black Aggie is the unauthorized—and cursed—copy of the funerary sculpture for Clover Adams (of the presidentially famous Adams family) who died by suicide. Legends say her eyes glow at night and make men go blind, that her shadow causes miscarriages, that sleeping on her lap causes death, and even that she tore her own arm off, giving it to a local metal worker. After enough incidents, the statue was removed from the cemetery and sequestered in the basement of the Smithsonian. She’s currently installed in the courtyard of the Howard T. Markey National Courts Building in Washington D.C. Photo: dbking on Flickr