Or, what I learned about creativity when my eyes were swollen shut

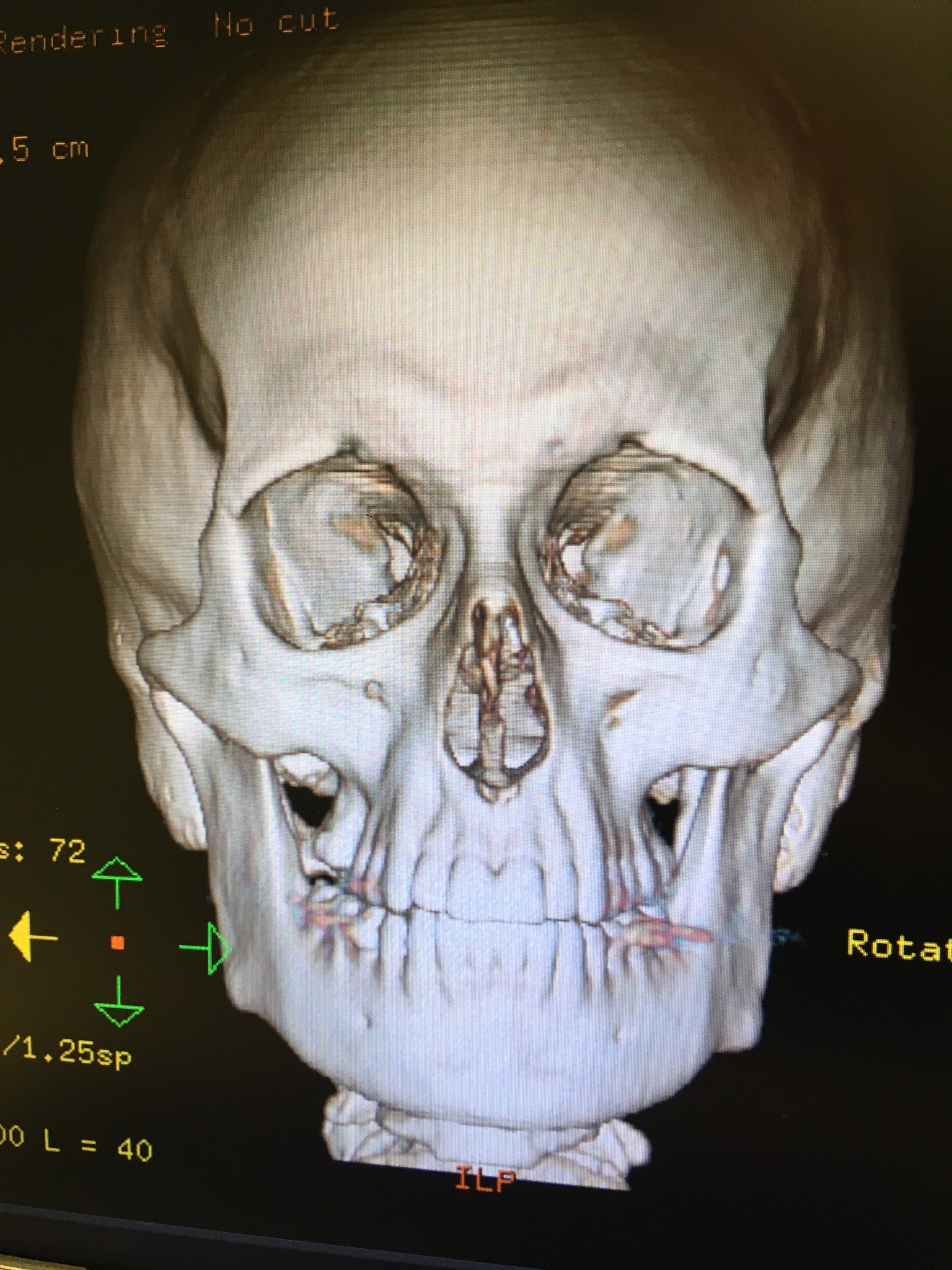

On Monday, December 28th I went under the knife for facial feminization surgery, and am currently recovering as I write this. It’s a weird time, under COVID, to undergo a surgery. Many of my friends surgeries were cancelled due to vanishing hospital capacity, and I was expecting the same up until the last minute. But because the procedure required no hospital stay, it went on. And while I felt guilty of using the services of doctors for this while so many people in Southern California needed treatment for a deadly disease, my friend reminded me that I’m not the one who makes the decisions regarding allocation of hospital resources, and this surgery is incredibly important to my health and well being. I’m so grateful that I have access to this with union health insurance, and I have my spouse to care for me while I recover. Access to this much-needed surgery is very limited for transgender people around the country and world, and that needs to change.

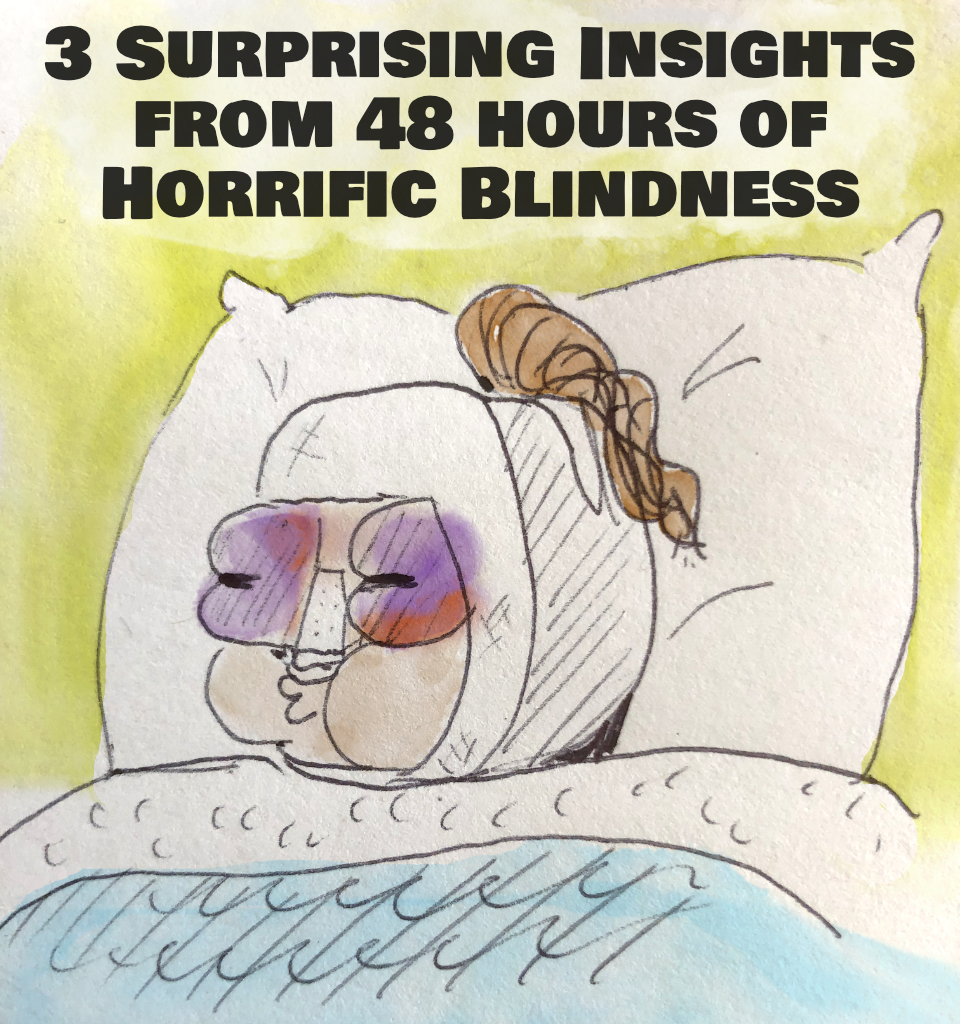

I was nervous about how rough the recovery would be, and it turned out I was right to be—it was worse than I thought. I was aware that I may have “disturbances in my vision” and that one of my eyes might be swollen shut, but I didn’t expect for both of my eyes to swell shut for so long, leaving me completely blind for 48 hours and with limited vision for 24 more. This was a terrifying and enlightening experience. I’m still recovering and staying in bed, and my face looks like a bruised balloon, but I’m happy to report I’m on the mend, and that the worst is over. Here’s what I learned from the worst:

Your imagination needs input, but also a lack of input to function; Your creativity is an organ, not a muscle

For awhile I’d been feeling like I’d been filling my mind with trash, afraid to be alone with my thoughts—and destroying and atrophying my creativity in the process. I was constantly doomscrolling the news, reading hot takes about the latest meaningless Twitter drama, filling my head with political podcasts, searching for content for posts, and swimming in the general shit-soup of social media.

I’d wanted turn to my attention toward enriching art and media to “fill the creative well”: read better books and more widely, watch worthwhile films, spend more time learning etc. But I’d forgotten about the mind’s need for boredom and low-input time to have it really go wild and be able to harness its imaginative powers.

I started hallucinating after being blind for about 8+ hours. I wasn’t surprised by this, as I’d read in Oliver Sack’s book Hallucinations (affiliate link), that the mind will create its own sensory data when a sense is cut off—but I hadn’t made the connection to my creativity, and the ability to visualize in the mind’s eye.

My uncontrolled hallucinations were generally abstract, or crowds of people and creatures rushing about, like the extras in a Where’s Waldo spread, but I soon found I could control what I was visualizing. I was able to perfectly render my Animal Crossing Island and play the game in my mind’s eye, and visualize scenes in the novella I’m working on as well. I’d been concerned that my abilities to visualize and imagine had diminished in 2020, but this showed me that my mind simply needed a break to do it’s job, and my visualization while writing and reading has improved since my sight returned.

My imagination and creativity hadn’t atrophied like I thought it had, it’s full capabilities are always there. Giving my imagination space to work didn’t have to be something as serious as mediation, I just needed to stop feeding it, so it had time to digest. Next time I’m feeling un-creative, instead of having surgery, I’ll just stare at a blank wall.

There’s No Substitute for Experience When Writing and There’s No Substitute for Writing Your Experiences

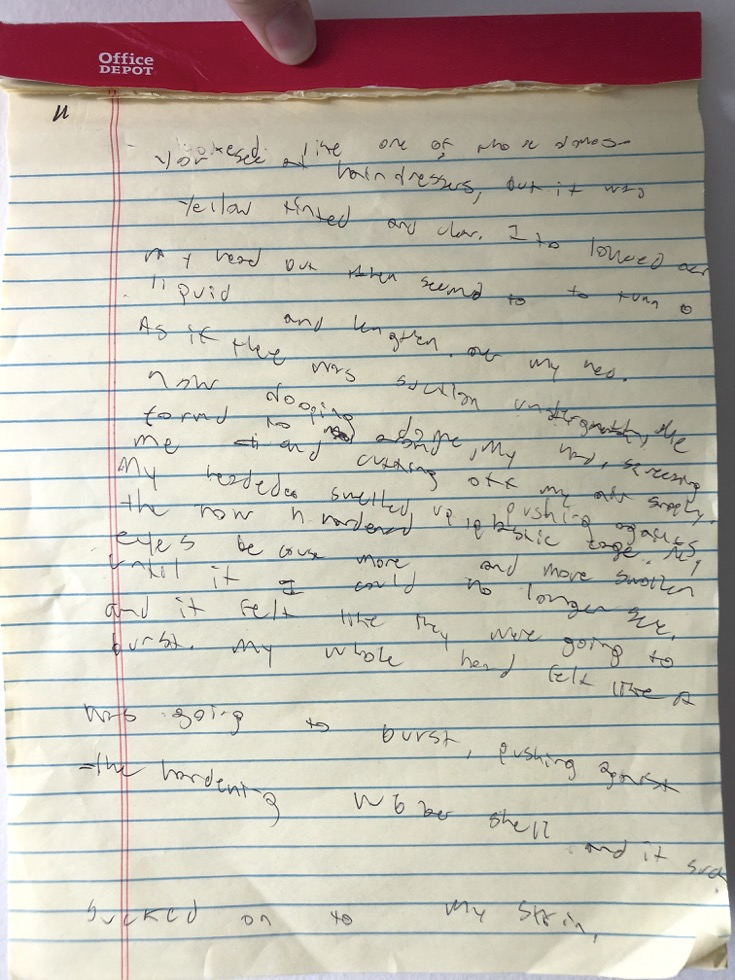

Just like it says, it’s hard to remember this fact until you’re going through it. The first 24 hours after surgery were really, really rough. The pain and swelling against my bandages felt uncontrolled and my loss of vision was terrifying. I was laughing at my pre-surgery naiveté, asking for Body Horror movie recommendations on social media, not fully comprehending that I was about to experience some very real-life body horror. And to deal with it, I decided to try and work on my novella on a yellow pad, even though I wouldn’t be able to see the words I was writing.

I’m currently in the middle of writing Transmuted, a novella about a trans woman who undergoes an experimental feminization treatment, after she loses the money she raised for FFS (the procedure I just had). While swelling, in agonizing pain, and unable to see, I wrote a scene for the novella, where the main character is subjected to a mad-scientist version of what I was experiencing, as a part of her treatment. I’ve since typed up those words, and they’re good first draft material on a scene I was a little stumped on. This book is written in first person present tense, and I believe this will be one of the most disturbing scenes in Transmuted. And the act of writing it was incredibly cathartic, as well.

I did try to write other scenes, but without my outline and limited concentration, I struggled and I don’t think those words are as usable. There is no doubt in my mind, that the experience allowed me to write the best version of that scene I could. And there’s no doubt that writing it down was what I needed most in that moment. Writing about this traumatic experience was not only easy, it was necessary. It’s not always appropriate to use your personal experiences in a story, but having the core of your story come from a place of lived experience can take a work to the next level.

You can improve with zero self-evaluation; the feedback loop is more complicated than we thought

This one was the most unexpected and interesting insights, and I think it applies broadly to any kind of creative practice. After the initial terror of being blind wore off, I found the experience of sightlessness to be predominantly boring. Because of a bandage around my chin, it was very tiring to talk, so all I could do was listen. The Ink Heist and This is Horror podcasts were indispensable to me, they kept me entertained, and helped me feel like I was still among my friends in the horror community even though I couldn’t reach out. A special shout out and thanks to Laurel, Shane, Rich, Michael, and Bob.

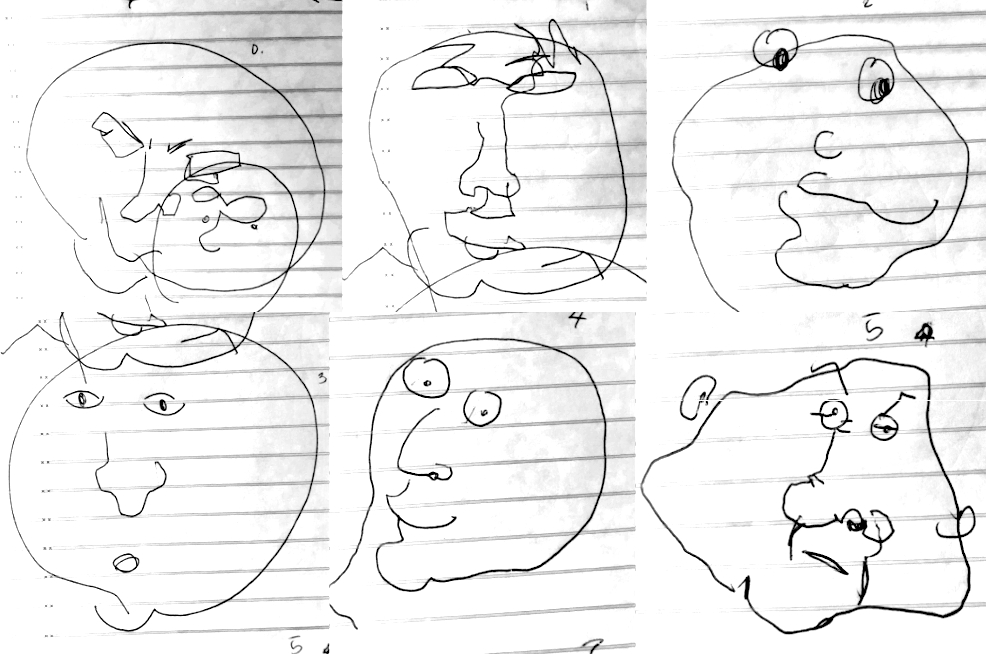

Another thing I did to pass the time was to draw. Even though I couldn’t see what I was drawing, and I expected the results to be disjointed scribbles, it was more entertaining than nothing to doodle on the page and try to draw the best possible faces I could. But while I was drawing, my spouse remarked that my drawings were getting better. This surprised me, as I had no way to judge how I did after I completed a drawing, and adjust what I was doing to improve the result.

I’d always believed that when developing a creative skill, the main way to improve is by practicing, evaluating your work based on your knowledge and tastes, and using that assessment to learn how to improve. But it seemed that I was improving without the evaluation stage. It’s possible this was a fluke, but I believe it’s a larger insight about the creative process. Merely the act of practicing and trying to improve, even if you never assess the resulting work, will improve your skill. The subconscious mind has insights that your conscious mind does not have access to, and perhaps the act of engaging a skill causes learning and improving. Or, perhaps the act of merely trying something with the intention of improving causes improvement.

I’m not really sure of what the implications are of this insight. Obviously, to improve your work, you should be evaluating it. Don’t stop doing that! But it made me wonder if the evaluation stage is less important than we thought—and if there is a benefit of having some of one’s creative exercises remain un-evaluated. What do you think? Is there insight to be found here? Or is this just a fluke? I’d love your thoughts.

I learned many other things during my experience, but they’re out of the scope of this post. Thanks so much for reading and feel free to reach out if you have feedback.