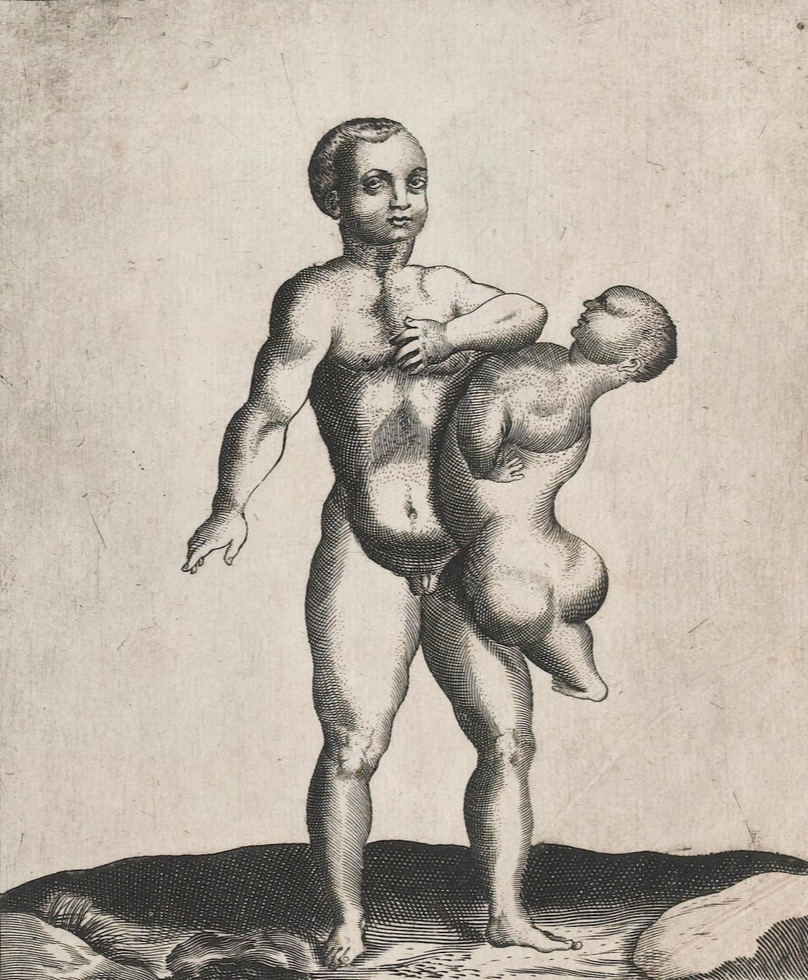

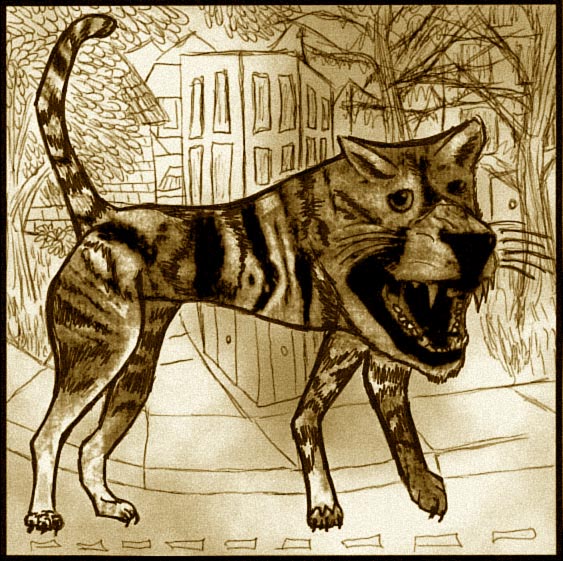

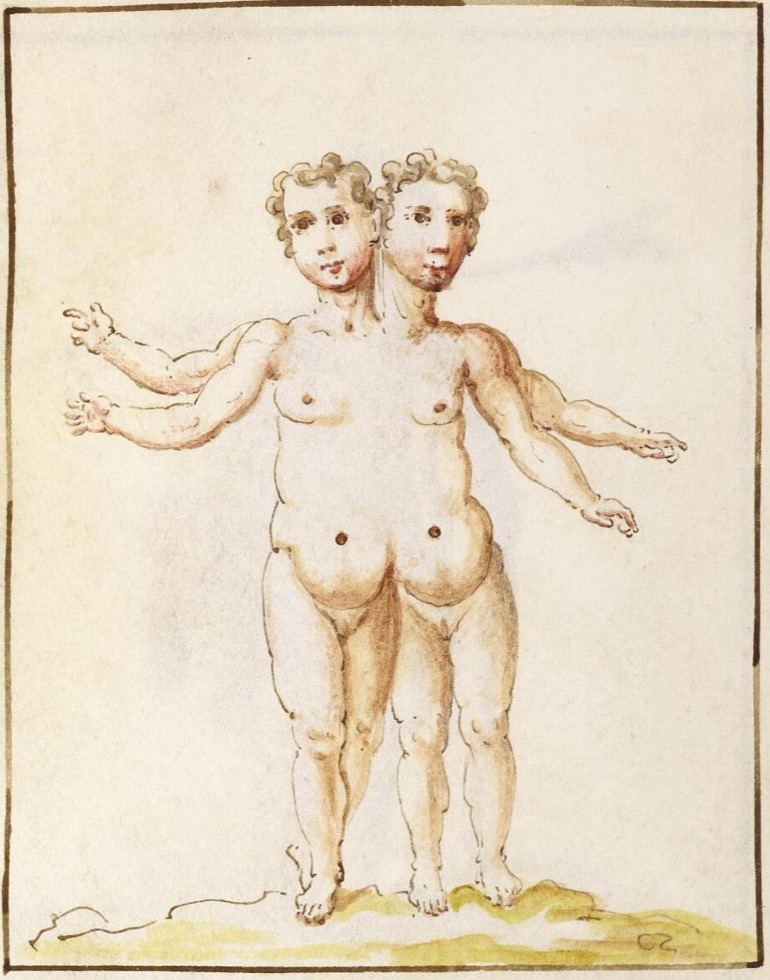

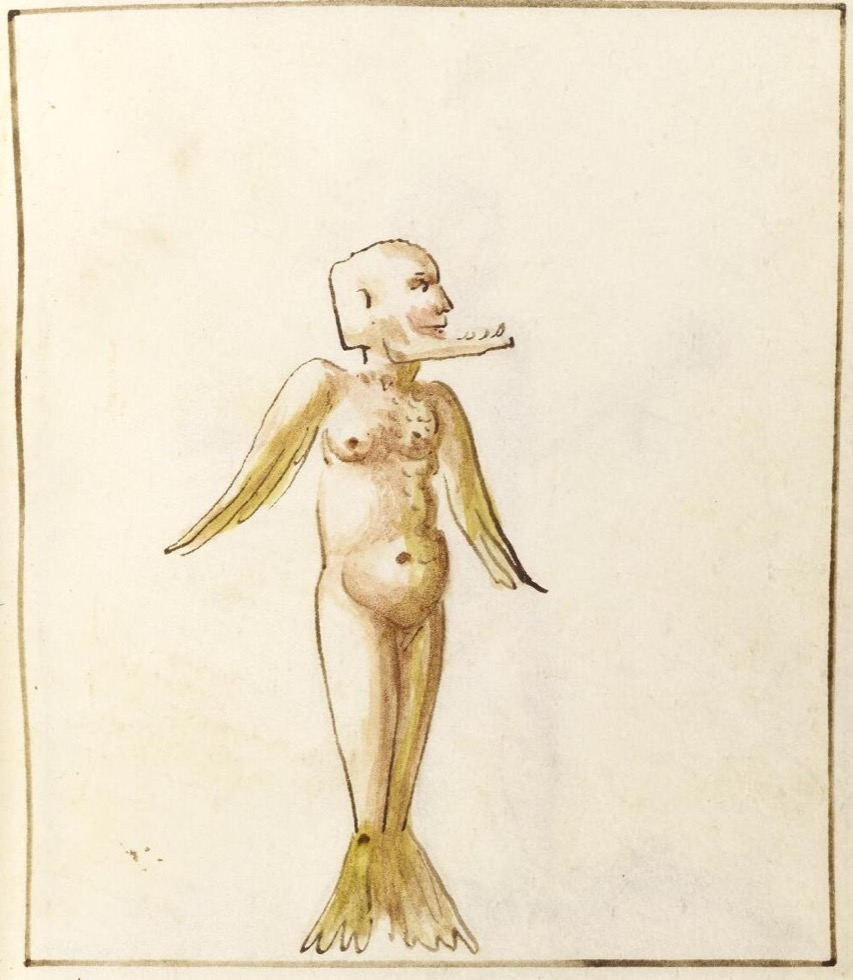

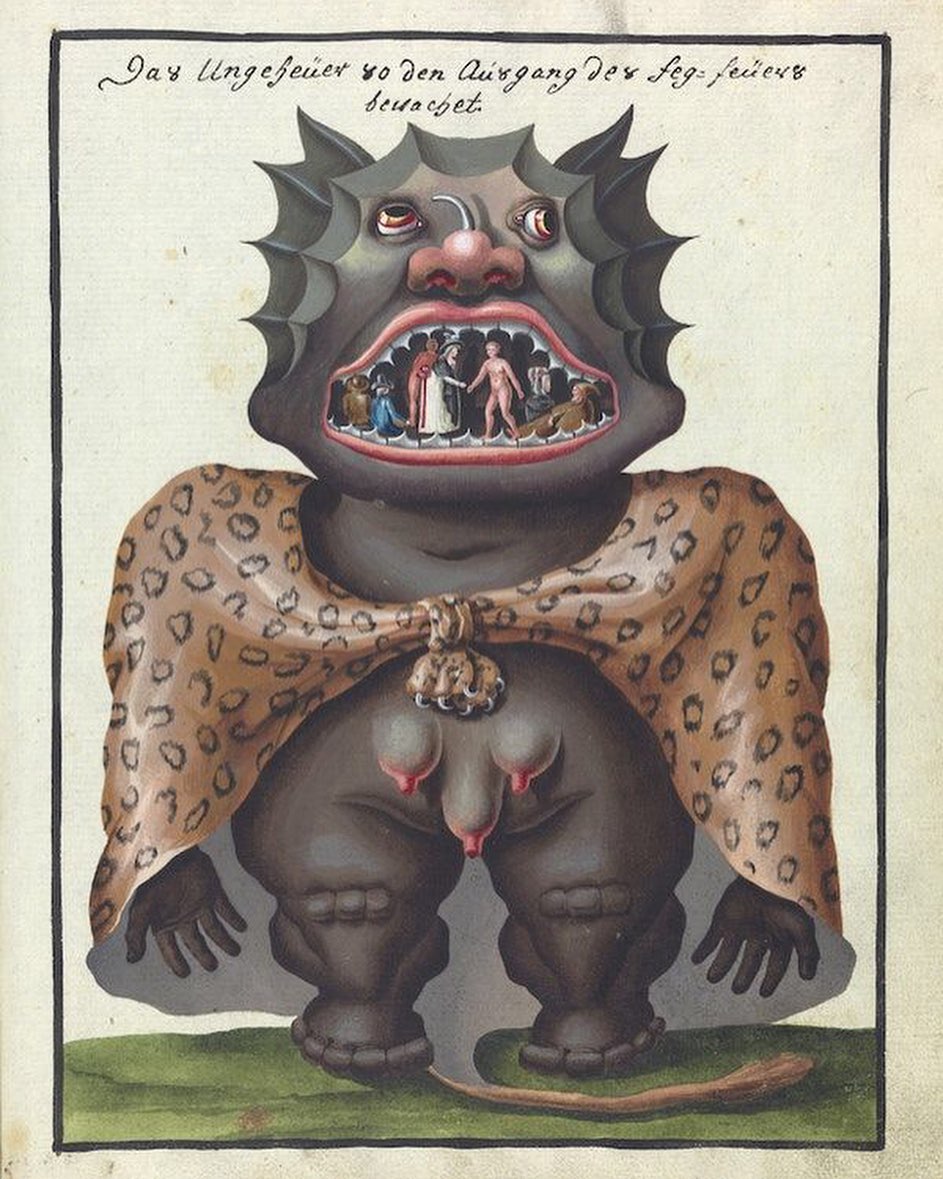

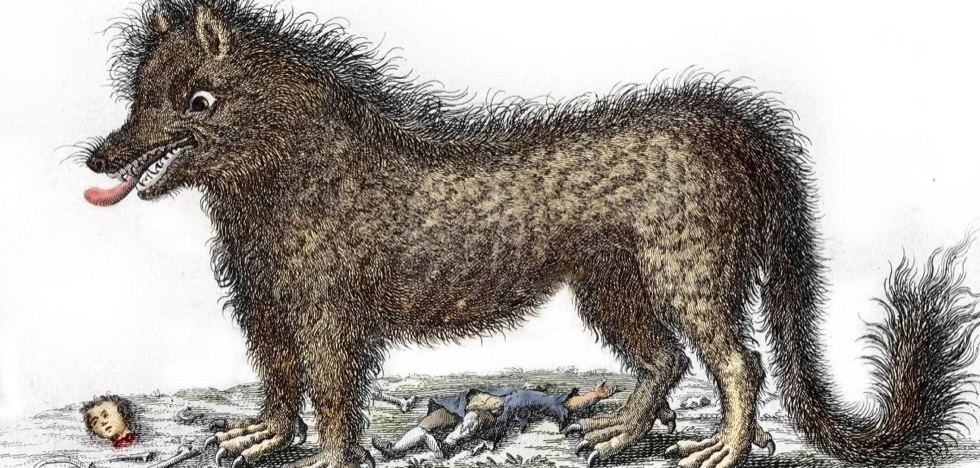

Engravings of hybrid monsters from Opera nela quale vi e molti mostri de tutte le parti del mondo antichi et moderni or “Work in which there are many monsters from all parts of the world, ancient and modern” by Giovanni Battista de’Cavalieri, 1585. Image: Wellcome Collection