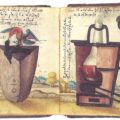

Catacomb saints are the lavishly decorated bodies of early Christians that were exhumed from the catacombs of Rome by the Vatican and placed in towns throughout Europe between the 16th and 19th century. The bodies were covered in gold and precious stones and acted as relics. Images: Neitram, Dalibri & Dbu (wikimedia commons)